An exotic fly species, the serpentine leafminer, Liriomyza huidobrensis, has been detected infesting field vegetables in western Sydney.

The serpentine leafminer is a pest with a wide host range, spanning vegetable, potato, nursery and broadacre cropping plant species.

While a biosecurity response is currently underway at the time of writing this article, here we investigate the potential impact from a grains perspective should this species establish in Australia.

Lifecycle and feeding symptoms

The serpentine leafminer belongs to a family of leaf-mining flies called ‘Agromyzidae’, which tunnel through internal plant tissue as larvae.

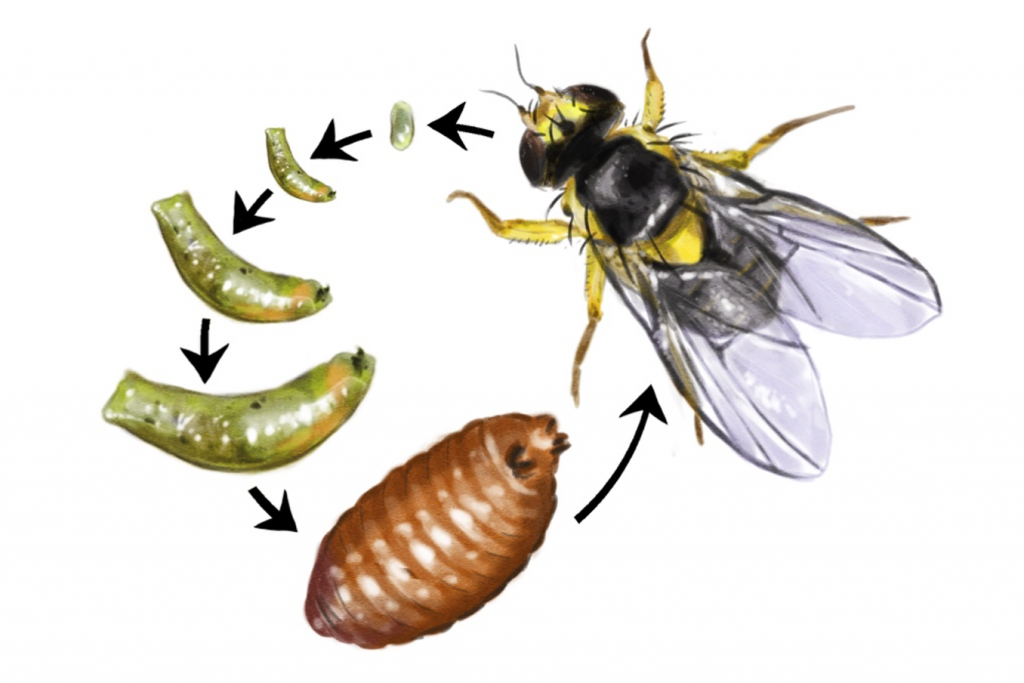

The serpentine leafminer fly lifecycle has four stages:

- Adults flies are small (1 – 2.5 mm in length) and black with yellow spots on the head and thorax. They feed on plants and lay microscope, translucent eggs inside plant tissue.

- The eggs hatch and larvae tunnel through plant tissue feeding. The larvae are legless about 3.5 mm long when mature found feeding inside the leaf. They change from creamy-white to pale yellow-orange as they grow through three instars.

- Once they approach maturity, the larvae cut a slit in the plant and drop to the ground to pupate. The pupae oval segmented and slightly flattened, dark brown to black between 1.6 mm and 3.3 mm in length.

- Adult flies emerge from pupae and mate

While adult feeding does create stippling symptoms and can expose plant to secondary infection, most damage occurs from larvae feeding and creating thick white trails called leaf mines.

Leaf mines can reduce the photosynthetic ability of the plant, and reduce the growth and development of seedlings and young plants. In severe cases, the miner feeding can lead to plant death.

Mining is usually restricted to the leaves; however, some legume pods can display symptoms.

Identifying the serpentine leafminer

Australia is already home to several native and introduced leafminer flies. Species that can occur within cultivated grains and pulses include the cabbage leafminer, Liriomyza brassicae, which attacks a wide range of brassica crops and can occasionally be found within canola, Ceradontha species leafminer which attack grasses and are occasionally found in cultivated grains such as wheat and barley, and the rice leafminer (Hydrellia spp) which can occasionally be found within rice. None are considered problematic pests.

This poses a problem for identification and detection of the serpentine leafminer because its leaf mines are indistinguishable by eye from many of those created by other species.

Furthermore, the serpentine leafminer itself, either as a larvae or adult, also can’t be distinguished by eye from other species present in Australia.

As a result of the difficulty in identifying the fly and its damage by eye, molecular diagnostics are essential.

Photo by National Plant Protection Organization, the Netherlands, Bugwood.org, CC BY-NC 3.0 US

Photo by Elia Pirtle, Cesar Australia

Potential to establish and spread in Australia

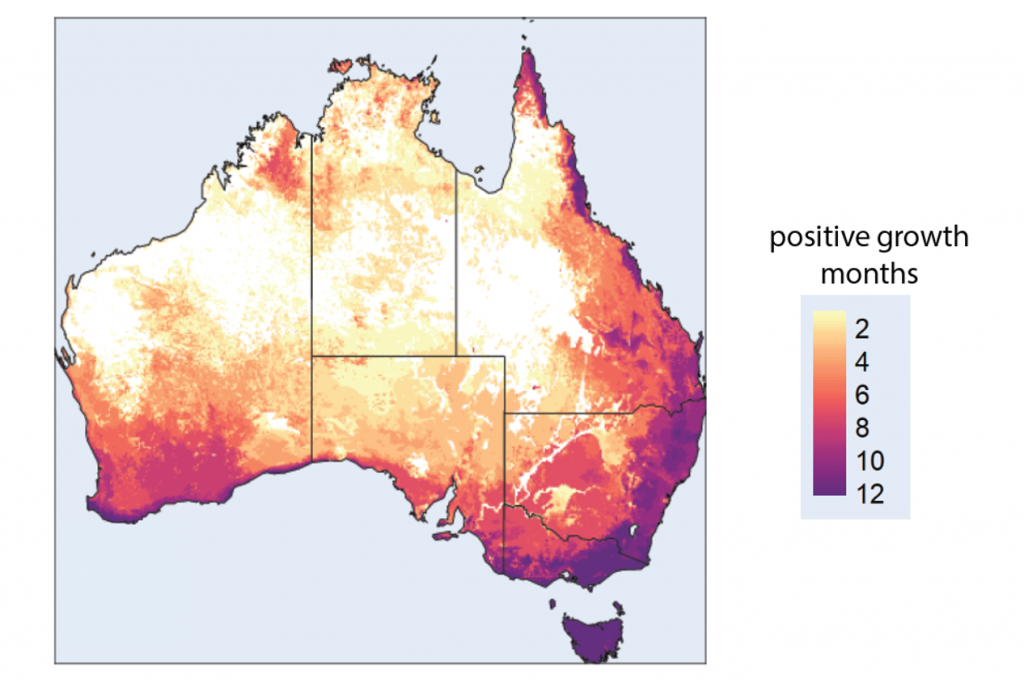

Using an Establishment, Spread, Impact and Management (ESIM) framework, Dr. James Maino at cesar has forecasted a risk profile for the serpentine leafminer. The forecast considers how the growth rate of the pest responds to temperature as well as mortality caused by environmental stressors, such as heat, cold and drought (all of which can be measured in a lab), and then determines what that means for the potential of the pest to survive across the year at locations all across Australia.

This forecasting work has shown that the serpentine leafminer has the potential to establish in many agricultural regions of Australia (Figure 1).

Upon establishing in a region, the primary method of spread is likely to be through movement of eggs and larvae on live plant material and cut flowers. Pupae may spread with soil. Adults can disperse by wind, but can also be spread via human assisted movement such as on goods, aircraft, vehicles and plant material.

Relevance to the grains industry

The serpentine leafminer has an extremely wide host range across at least 15 plant families, which including many economically important crops.

However, the economic damage to broadacre crops is very unlikely to be as significant as it will be to vegetable, potato and nursery crops.

With respect to broadacre crops, based on the frequency of appearance in published host reports internationally, serpentine leafminer is expected to prefer pulses (particularly faba beans, and soybeans) over wheat, barley, oats, rice, and corn.

While serpentine leafminer does show preference for several brassica crops, canola is not widely reported as a host, and is expected to be at lower risk than vegetable brassicas due in part to the timing of the growing season.

Prospects for management in grains

At this stage it is too soon know if the serpentine leafminer will be an issue for the grains industry given that we are still in the midst of a biosecurity to response to contain or even eradicate the leafminer.

Should the serpentine leafminer require management in broadacre crops in the future, an integrated pest management approach will likely be necessary.

Research suggests that endemic parasitoid wasps in Australia will play a vital role in the control of the serpentine leafminer should be species become established.

Australia has at least 50 species of parasitoid wasps that attack native leafminer flies. Of these, some species including Hemiptarsenus varicornis, Diglyphus isaea and Opius spp., are known to be particularly important for exotic leafminer management overseas.

Cultural control methods would also play an important role in control, including removal of alternate hosts and weeds from production areas.

In many countries, reliance upon insecticides as the main control method for leafminer pests has led to other Liriomyza species evolving resistance to several mode of action sub-groups.

Contact insecticides control leafminers poorly as they only kill adults. Insecticides must be systemic or translaminar to effectively control leafminer larvae.

Report suspect serpentine leafminer

You can report any signs of leaf mining in vegetables to the Exotic Plant Pest Hotline on 1800 084 881. Photos of damage and leafminers can be sent to biosecurity@dpi.nsw.gov.au

Further resources

Management of leafmining flies in vegetable and nursery crops in Australia

Serpentine leafminer: A threat to the potato industry

Acknowledgements

The project RD&E program for control, eradication and preparedness of vegetable leafminer (MT16004) has been funded by Hort Innovation using the vegetable, nursery, melon, and potato research and development levies and contributions from the Australian Government. Hort Innovation is the grower-owned, not-for-profit research and development corporation for Australian horticulture.

Cover image: Photo by Central Science Laboratory, Harpenden, British Crown, Bugwood.org, CC BY-NC 3.0 US