Yellowheaded cockchafer

Sericesthis harti, Sericesthis spp.

Other common names

Scarab

Photo by Andrew Weeks, Cesar Australia

Summary Top

Yellowheaded cockchafer (Sericesthis harti) is the main species of white curl grub affecting cereal crops across south-eastern Australia including New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia. However, there are many related Sericesthis spp. They are predominantly a pest in cereals but may also attack pastures. Spring-prepared fallows will help reduce damage in the following year. Intensive crop rotations and short pasture rotations can also be used to prevent future damage. Control with foliar insecticides is not possible as the larvae live exclusively in the soil, although seed treatments are now available for low to moderate populations.

A native species that became a pest with the reduction of spring-prepared fallows before sowing cereals. They are a minor pest, restricted in range and regularity.

Occurrence Top

The yellowheaded cockchafer is a sporadic agricultural pest found in parts of New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia. Larvae live in the soil until mid-late summer when they emerge as adult beetles.

Description Top

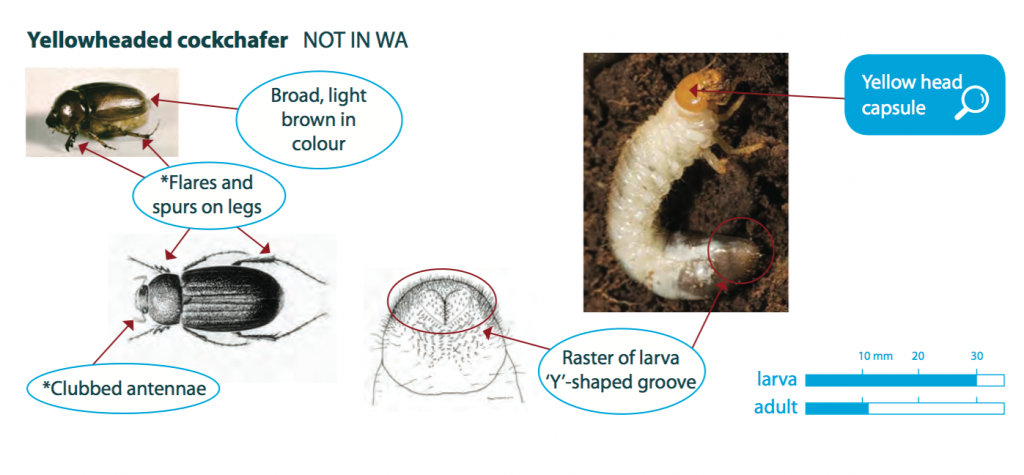

Yellowheaded cockchafer larvae are creamy-grey in colour with a yellow head, have six legs, a yellow head capsule and curl into a “C” shape when disturbed. When fully grown in winter larvae are 25-30 mm long. Their body is white grey when feeding and turns to a creamy-yellow colour as they mature. Their brown gut contents show through the clear skin. The larvae are soil-dwelling and do not come to the surface. The adult cockchafer beetles are chunky and yellow-light brown beetles about 10-15 mm in length. They have long fine legs with ‘flares/spurs’ and clubbed antennae.

Lifecycle Top

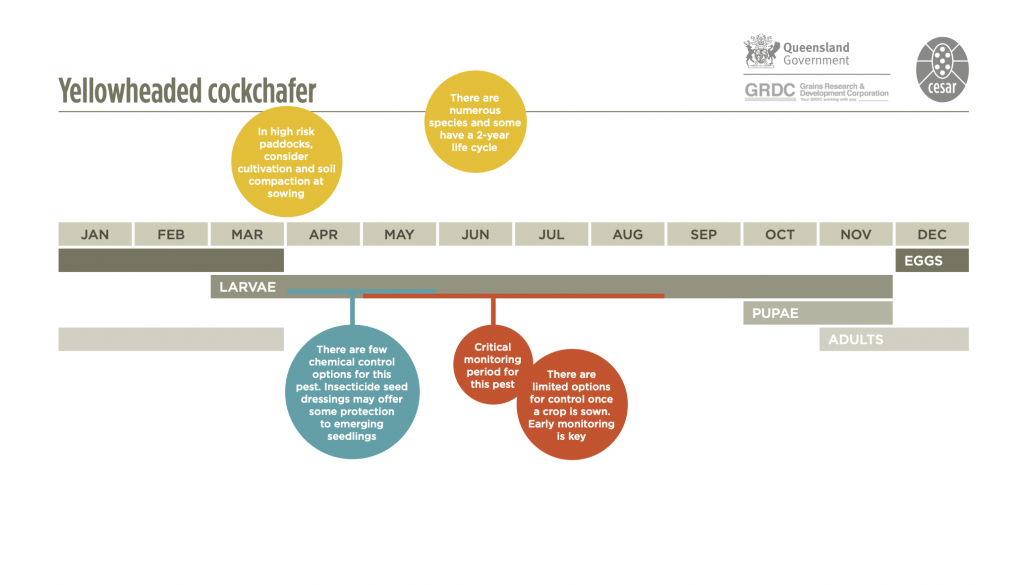

There has been no published research on this pest. Hence, the biology of the species is not well understood but it is thought to have a two-year lifecycle (Bailey 2007).

Adults generally emerge from the soil at dusk during November to early December forming flights to mate. They then lay eggs in the soil to begin the next generation, preferring grass pastures over bare ground or legume dominant pastures. Eggs hatch in spring and larvae reach the third and last larval stage by the end of autumn or in early winter, taking about 10 months to reach maturity. Third-stage larvae feed during winter causing most of the damage to cereals. Pupation occurs in mid-late spring, with adults again emerging from the pupae in November/December to lay the next generation eggs.

Adults prefer to lay in grass pastures over bare ground.

Behaviour Top

The larvae spend their complete life in the soil from late autumn until mid-to-late summer, feeding on soil organic matter and plant roots. Providing the air temperature and wind speed are favourable, the mating flights of adults can form very dense flights with each flight usually lasting for about 15 to 30 minutes. Adults can also fly long distances.

Control with foliar insecticides is not possible as larvae live exclusively underground.

Similar to Top

Other scarabs beetles and cockchafers, including white curl grubs with ‘yellow’ head capsules (e.g., wheat root scarab (S. consanguinea) and black soil scarab (Othnonius batesii)). The redheaded pasture cockchafer (Adoryphorus couloni) and the blackheaded pasture cockchafer (Acrossidius tasmaniae) have darker head capsules but are also easily confused. Adults can be confused with dung beetles.

Crops attacked Top

Primarily cereal crops, but also pastures.

Damage Top

The soil dwelling yellow-headed cockchafer larvae either damage plants by feeding directly on the roots of a wide range of pasture and crop plants, including all cereals, or damage roots while they are foraging for decayed organic matter in the area. Third-instar larvae feeding during winter and early spring are most damaging.

Moisture stimulates the larvae to move closer to the soil surface in autumn where they feed on the roots of newly emerging seedlings. Feeding (root pruning) causes weakening of plants, wilting, and eventually plant death. While damaged plants may initially grow normally, they will often wither then die at tillering leaving bare patches in the crop and re-sowing may be required. Severe infestations can result in complete crop loss. Damage is worse under drought conditions as plants lose the ability to replace severed roots. Crops sown into long term pasture paddocks are most vulnerable to attack. Higher seeding rates can reduce levels of damage.

Be aware that if problems with yellowheaded cockchafers did not occur in the preceding year, it does not mean that this pest will not be an issue in the current season. Adult beetles achieve long distance dispersal by flying, usually at dusk on warm evenings in late spring-early summer, and can therefore move into a paddock from a source elsewhere.

Monitor Top

Crops sown into long term pasture paddocks are vulnerable to attack. Monitor susceptible paddocks prior to sowing and throughout winter. Inspect paddocks by digging to a depth of 10-20 cm with a spade and counting the number of larvae present. This should be repeated 10-20 times across paddocks to get an estimate of larval numbers. Four larvae per spade square is roughly equivalent to 100 larvae per m2. 30 larvae per m2 can potentially reduce yields by up to 1400 kg/ha. Yellowheaded cockchafer numbers increase following dry springs and summers, particularly after a succession of dry years. Birds foraging in the soil after ploughing indicate the presence of insects and provide a good cue to inspect the soil for pests of germinating cereals.

Economic thresholds Top

There are no economic thresholds available for this pest.

Management options Top

Biological

Birds, parasitic wasps and flies are the most effective natural enemies. Birds prey on larvae and are most valuable after cultivation. Metarhizum spp. are pathogenic fungi that can attack and reduce pasture cockchafer populations. To help facilitate biological control, existing on-farm native vegetation should be preserved, and breeding habitats for birds and parasitic insects should be maintained.

Cultural

Intensively grazing in spring, summer and autumn will make eggs and larvae in the topsoil more susceptible to desiccation and predation. Cereal crops following several years of pasture are most susceptible. Spring-prepared fallows will help reduce damage in the following year. Intensive crop rotations and short pasture rotations can also be used to prevent future damage. Re-sowing affected areas with a higher seeding rate will assist plant establishment. Cultivation will directly kill larvae and expose them to predation.

Chemical

A new mixed formulation product has recently been registered as a seed protectant against yellow headed cockchafer in pastures. Control is expected for 3-4 weeks after sowing, but will not control heavy populations. Larvae live underground and are unlikely to be affected by foliar applications of insecticides.

Spring-prepared fallows will help reduce damage in the following year. Intensive crop rotations and short pasture rotations can also be used to prevent future damage.

Acknowledgements Top

This article was compiled by Paul Umina (cesar) and Bill Kimber (SARDI).

References/Further Reading Top

Allen P. 1986. Yellowheaded cockchafer. Department of Agriculture South Australia. Fact Sheet FS 23/85.

Bailey PT. 2007. Pests of field crops and pastures: Identification and Control. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, Australia.

Bellati J, Mangano P, Umina P and Henry K. 2012. I SPY Insects of Southern Australian Broadacre Farming Systems Identification Manual and Education Resource. Department of Primary Industries and Resources South Australia (PIRSA), the Department of Agriculture and Food Western Australia (DAFWA) and cesar Pty Ltd.

Department of Primary Industries NSW. Establishing pastures – Readers’ Note.

http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/163118/establishing-pastures-1-7.pdf

Goodyer GJ and Nicholas A. 2007. Scarab grubs in northern tableland pastures. New South Wales Department of Primary Industries. Primefact 152. http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/110213/scarab-grubs-in-northern-tableland-pastures.pdf

Henry K, Bellati J, Umina P and Wurst M. 2008. Crop insects: the Ute Guide, Southern Grain Belt Edition. Government of South Australia PIRSA and GRDC.

| Date | Version | Author(s) | Reviewed by |

|---|---|---|---|

| December 2014 | 1.0 | Paul Umina (cesar) and Bill Kimber (SARDI) | Garry McDonald (cesar) |

What are PestNotes?

PestNotes are information sheets developed through a collaboration between Cesar Australia and the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI). Copyright: © All material published in PestNotes is copyright protected by Cesar Australia and SARDI and may not be reproduced in any form without written permission from both agencies.

Disclaimer

The material provided in PestNotes is based on the best available information at the time of publishing. No person should act on the basis of the contents of this publication without first obtaining independent, professional advice. PestNotes may identify products by proprietary or trade names to help readers identify particular products. We do not endorse or recommend the products of any manufacturer referred to. Other products may perform as well as or better than those specifically referred to. Cesar Australia and PIRSA will not be liable for any loss, damage, cost or expense incurred or arising by reason of any person using or relying on the information in this publication. Any research with unregistered pesticides or products referred to in PestNotes does not constitute a recommendation for that particular use.